Source: Human Rights Watch Report “Razed to the Ground – Syria’s Unlawful Neighborhood Demolitions in 2012-2013”, January 2014

2. Demolitions

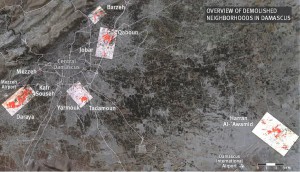

One of the few attempts to contextualise satellite images and maps of destruction in Syria was a 2014 report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) titled “Razed to the Ground: Syria’s Unlawful Neighborhood Demolitions in 2012-2013.”1 The report documents seven cases of large-scale demolitions of thousands of residential buildings in Damascus and Hama in 2012 and 2013 by the Syrian authorities, using explosives and bulldozers in violation of international law.2

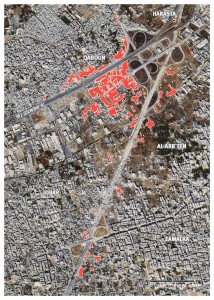

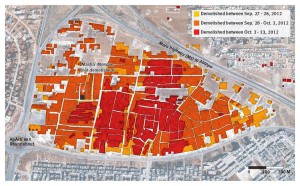

Demolitions in Qaboun district, Damascus. Approximate dates of demolitions: 12 July-October 2012 and June-July 2013. Estimated area demolished: 18 hectares.

Source: Human Rights Watch Report “Razed to the Ground – Syria’s Unlawful Neighborhood Demolitions in 2012-2013”, January 2014.

The 38-page report is based on detailed analysis of 15 high-resolution satellite images, which were compared to the witness accounts of 16 interviewees, as well as a review of media reports, government decrees and videos of the destruction and its aftermath posted on YouTube.

Syrian regime officials and pro-regime media outlets claimed at the time that the demolitions were part of “urban planning” schemes concerning “illegally constructed buildings” (more on this below). However, the report points out that the demolitions were supervised by military forces and often followed fighting in the areas between government and opposition forces. Indeed, all of the seven neighborhoods examined in the report were widely considered by the authorities and by witnesses interviewed by HRW to be “opposition strongholds.” In addition, there had been no similar demolitions in areas loyal to the regime, even when many houses in those areas were illegal too.

A Wall Street Journal article from November 2012 observed, “based on several extended visits to Damascus and vicinity last month – some of which coincided with demolition by military authorities – the destruction appears to be occurring only in areas where opposition fighters have been active.”3 In fact, some of owners of the demolished houses interviewed by HRW claimed that they did possess all the necessary permits and documents for their houses. Moreover, none of the victims received adequate notice, consultation or compensation. The report therefore concludes that the demolitions were in violation of international law because they “either served no necessary military purpose and appeared to intentionally punish the civilian population or caused disproportionate harm to civilians.”

Demolition in Masha` al-Arb`een district, Hama. Estimated destruction area: 40 hectares.

The cases examined by HRW seem to fall into two categories: “punitive” and “anticipatory.” Some of the demolitions appear to have served no necessary military purpose and were merely intended to punish the civilian population for past actions. This is the case with the Masha’ al-Arb’een and Wadi al-Joz neighbourhoods in Hama and the Tadamoun and Qaboun neighborhoods in Damascus. Under international law, undefended or demilitarised areas are considered civilian objects, and should not therefore be targeted. International law also prohibits the punitive destruction of property.

Others appear to have been prompted by military considerations (areas close to military or strategic sites that opposition forces had either attacked or could attack). This is the case of the areas surrounding the Mazzeh military airport, the Damascus international airport and the Tishreen military hospital. But while the authorities may have been “justified in taking some targeted measures to protect these military or strategic locations,” the report argues that the destruction of hundreds of residential buildings, in some cases kilometers away, were disproportionate and in violation of international law.

The authors of this report would argue that the demolitions examined by HRW and other similar cases are linked to the armed conflict in two other ways (not just collective punishment and disproportionate harm).

Firstly, the targeting and destruction of certain neighbourhoods appears to have been intended to not only punish the communities supporting the revolution or the armed rebels, the majority of which happened to be Sunni, but also to ‘cleanse’ those areas of all ‘unwanted elements’ and prevent them from coming back in the future and repeating the same story again. The result is changing both the political alliances and the demographic composition of those areas. Homs is a good example of this.4

In its ninth report,5 released in February 2014, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria outlines the pattern that often preceded planned demolitions:

9. By late 2012, government forces had changed tactics and rarely engaged in ground attacks. This appeared motivated by the fact that ground attacks provided the infantry, which was majority Sunni, with opportunities to defect and by the increased capacity of armed groups to attack government units.

10. Nevertheless, the mainstays of government attacks on restive areas have remained static. They include (a) the encirclement of an area, including the setting up of checkpoints at all access points; (b) the imposition of a siege, including preventing the flow of food, medical supplies, and sometimes water and electricity, into the town or area; (c) the shelling and aerial bombardment of the besieged area; (d) the arrest, and often disappearance, of wounded persons attempting to leave the besieged area to seek medical treatment no longer available inside and of those attempting to break the siege, usually by smuggling in food and medical supplies. Victims have often described the Government’s strategy as that of “tansheef al bahar”, or draining the sea to kill the fish. […]

Aleppo residents watching an air raid over Aleppo by regime forces. Source: Daily Telegraph, 2 February 2014. © Reuters/Saad Abobrahim

13. The Government’s use of indiscriminate shelling and aerial bombardment has been informed by its use of a variety of weaponry. The Government began hostilities by employing artillery shells, mortars and rockets against restive and sometimes besieged areas. By mid-2012, the use of cluster munitions, thermobaric bombs and missiles was documented, often used against civilian objectives, such as schools and hospitals. The Government has also used incendiary weapons. 14. The first reported use of barrel bombs was in August 2012 in Homs city. It was not, however, until mid-2013 that government forces began an intense campaign of barrel bombing of Aleppo city and governorate. […]

Secondly, at least in some areas, it appears that the war was utilised as an excuse or a cover to implement long-term or pre-existing plans of sectarian cleansing and demographic change.

In most of the cases examined by HRW, there was often a second wave of demolitions following the initial one, not justified by the war and not linked to the hostilities. Satellite imagery often showed neat piles of rubble, indicating that the demolitions were carried out in a “controlled and professional manner.” More importantly, at least in some cases, there had already been plans to ‘reconstruct’ the area for political purposes, as the following sections will show. The Mazzeh area in Damascus provides a good example of this.

To achieve this double aim of cleansing rebel areas and implementing long-term plans of demographic change in those areas, destruction and demolitions had to be followed by ‘reconstruction’ projects. The following sections will outline how these were planned and carried out.

Notes & References:

1. Available here.

2. The neighbourhoods examined in the report are: the Masha’ al-Arb’een and Wadi al-Joz neighborhoods in Hama, and the Qaboun, Tadamon, Barzeh, Mazzeh military airport, and Harran Al-‘Awamid neighborhoods in and near Damascus.

3. Available here.

4. See, for example, this Telegraph article.

5. Available here.

English

English  فارسی

فارسی  العربية

العربية